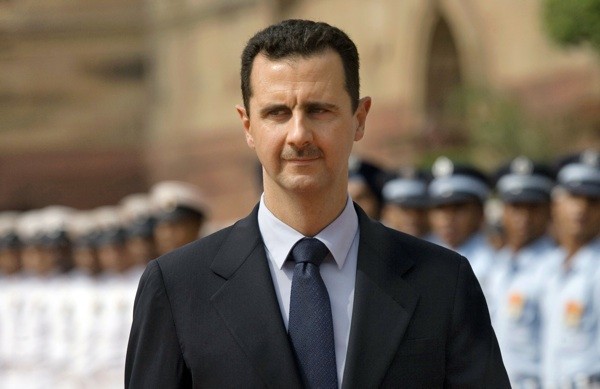

Brussels – Creating the conditions for the “safe, voluntary, and dignified repatriation” of Syrian refugees: this is the path that European governments are increasingly determined to pursue, now more than ever, in light of a possible wave of arrivals of Syrian refugees fleeing southern Lebanon torn apart by Israeli bombs. The problem, however – as human rights organizations denounce – is that the situation in Damascus has not changed, and returning Syrians risk violence and persecution from Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Or the armed groups that control part of the territory.

The idea of revising the EU Strategy on Syria, adopted in 2017, has been circulating in Brussels for some time. According to estimates by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), European countries host more than one million Syrian asylum seekers, 59 percent of them in Germany alone. The issue of Syrian refugee repatriation “is made even more urgent by the evolving hostilities in the Middle East and Lebanon,” diplomatic sources admit, as Lebanon, according to the UNHCR, is reportedly hosting more than 1.5 million refugees from Syria.

At the April European Council, leaders had put down on paper the “need” to set repatriations in motion “in line with the conditions defined by UNHCR,” calling on the European Commission to “examine and strengthen the effectiveness of EU assistance to Syrian refugees and displaced persons in Syria and the region.”

The European Commission seems determined to follow up on its call to set up a “more realistic approach” to relations with Damascus, a “more active, results-oriented and operational” strategy aimed at ensuring the safe return of refugees from the war that began in 2011. According to reports yesterday (Oct. 30), during a meeting with the ambassadors of member countries, the EU executive presented a new informal paper to test the positions of the 27 member states on the issue. The non-paper from Brussels would reflect “to a large extent” proposals made in July by the Italian and Austrian governments, in particular the hypothesis of an EU Special Envoy to the country, support for the private sector, cooperation with UNHCR on the ground to facilitate voluntary returns and to support the emergency through ‘early recovery projects.

From the exchange of views between the EU diplomatic corps, “broad support for the outlined plan of action” allegedly emerged, EU sources confirmed, emphasizing coordination with UNHCR while also expressing caution to avoid any perception of normalization of relations with the Assad regime.

On the other hand, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees notes that “despite several policy initiatives over 2023, conditions inside Syria are still not favorable to facilitate large-scale voluntary returns in safety and dignity.” According to UNCHR data, some 38,300 refugees returned to Syria in 2023, down from nearly 51,000 who chose to return in 2022. For now, UNHCR has not changed its March 2021 updated position that Syria is not a safe country for returns.

Several international organizations share this position, including Human Rights Watch, which, in a report released yesterday, pointed out that “Syrians fleeing the violence in Lebanon risk repression and persecution by the Syrian government upon their return.” According to the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC), between Sept. 24 and Oct. 22, about 440,000 people -more than two-thirds are Syrians, and the remaining Lebanese – flew from Lebanon to Syria. Although Damascus has so far kept “borders open and eased immigration procedures,” Human Rights Watch argues that “the Syrian government and armed groups controlling parts of Syria continue to impede humanitarian and human rights organizations from full and unimpeded access to all areas, including detention sites, hampering documentation efforts and obscuring the true extent of abuses.”

According to the human rights organization, those returning to Syria, “particularly men, risk arbitrary detention and abuse by authorities.” Human Rights Watch has documented numerous cases of arbitrary detention, torture, and killing of refugees returning since 2017. The report points the finger at “some European leaders” who “increasingly claim that Syria is safe for returns, promoting policies that could lift protections for refugees, despite ongoing security and human rights concerns.”

English version by the Translation Service of Withub

![Una donna controlla le informazioni sul cibo specificate sulla confezione [foto: archivio]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Etichette-alimentari.jpg)