Brussels – Five years have passed since that “new dawn for the United Kingdom” invoked by the former Conservative leader, Boris Johnson, after winning the election on December 12, 2019, the last before the country’s exit from the European Union. A lot has changed since then: three governments in London, Brexit materialized by January 1, 2021, and three years of more than rocky relations with Brussels. More importantly, the complete reversal of the balance of power between the Conservatives and the Labour Party, which now widely leads the polls after the Tories’ inexorable collapse. A constant between pre- and post-Brexit in the UK, however, remains Nigel Farage, the sovereignist, populist, and nationalist politician who most demonized the European Union and who accomplished his mission of enshrining London’s farewell with a referendum. In the July 4, 2024 election, he – and his Reform Party – is still the variable to watch out for in terms of the UK’s future.

The United Kingdom has an electoral system that is first past the post or a dry majoritarian: in each of the 650 constituencies in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, the candidate who gets more votes than the others is elected MP. The party that wins a majority of seats in the House of Commons (the minimum threshold is 326) wins the election and can form the government, with the Prime Minister technically appointed by the monarch according to the outcome of the vote. The polls for the July 4 election are open from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. local (8 a.m. to 11 p.m. Brussels time), but British voters can alsi vote by mail or proxy. When the polls close, the exit poll — the survey conducted among voters in about 150 constituencies, chosen to be demographically representative of the country — will be announced. After that, the counting of ballots will begin, which will last throughout the night: by early morning (July 5), it will be clear which party has a majority and approximately how many seats, while the final results are expected by late morning.

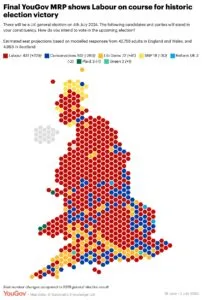

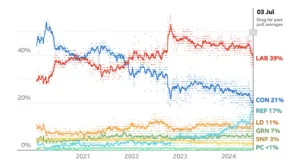

According to the latest surveys – confirming the outcome of the May administrative vote – Labour’s Keir Starmer is projected to a comfortable victory with 39 percent of the vote, ahead of the Conservatives of the outgoing Premier, Rishi Sunak (21 percent), by nearly 20 percentage points. Translated into a first past the post system, this should mean 431 for Labor (+229 from 2019) and a collapse to 102 for the Tories (-269), the worst result ever since the Conservative-Labor challenge (i.e., since 1922). However, the focus will also be on other parties in the race, which, even this time, will not break the traditional British bipartisanship but could create a crisis. In addition to the usual Liberal Democrats (seen rising to 11 percent, with 72 potential seats) and the Scottish National Party (in sharp decline also in Scotland, with a loss of an estimated 30 seats estimated, to 18 percent), there is also Farage’s sovereignist and populist Reform UK party. Formed from the spillover from the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and the former Brexit Party between 2018 and 2021, Farage’s party in the uninominal system is not expected to take home more than three seats, but it is the percentages that make the Conservatives tremble: with 17 percent of the total preferences, the Reform Party would come within just 4 percentage points of the Tories, and from there, an unpredictable process of convergence – if not merger – could begin between the more right-wing wing area of PM Sunak’s party (which risks not being elected in his Richmond constituency) and the Euroskeptic, anti-immigration, right-wing populists.

(source: BBC)

Three-and-a-half years after the start of the post-Brexit relations between Brussels and London, a landslide victory for Labour – that is set to return to 10 Downing Street after a 14-year absence – will not mean the beginning of a process to reintegrate the UK into the European Union. “I have been very clear that I do not intend to rejoin the EU, the Single Market, or the Customs Union, or allow a return to freedom of movement,” Starmer told the press yesterday (July 3). Even given the almost total absence in the campaign of issues related to Brexit and relations with the EU, it is clear that Labour has been trying to avoid the mistake of five years ago, when the former leader, Jeremy Corbyn, had aligned the consensus of a large section of the British electorate by promising a second Brexit referendum.

However, the incumbent Labour leader did not rule out that the – probable – next government he presides over will push for a more constructive dialogue with Brussels than the three previous Conservative-led executives (between Johnson and Sunak, there was Liz Truss, who lasted just 45 days): “I think we could get a better deal than the one bungled under Johnson on the trade, R&D, and security front,” Starmer made clear. London has been undergoing a strategy rethink vis-à-vis Brussels for the past year, with the Sunak government first reaching a political understanding with the European Commission on participation in Horizon Europe and Copernicus programs (starting January 1, 2024) and then on cooperation between Frontex and national authorities.

The Difficult Post-Brexit relations etween the EU and the UK

Since Brexit became a reality, the entry into force of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement made relations between Brussels and London particularly tense. The dispute began in March 2021, around the issue of the Irish Sea trade grace period, or the duration of the temporary concession to EU controls on health certificates for trade from Britain to Northern Ireland. In the post-Brexit context, these controls were necessary to keep the Single Market on the island of Ireland intact. The biggest problem involved chilled meats, and this is why there was often talk of a ‘sausage war’ with Brussels.

The attempt to unilaterally extend the grace period by the former Johnson government triggered a diplomatic clash between the two sides of the Channel, apparently resolved between July and October 2021. The EU executive suspended infringement proceedings against London to seek compromise solutions in all sensitive areas. But in June 2022, the EU Commission thawed the infringement proceedings, activating two more over London’s decision to try the unilateral amendment route to the Northern Ireland Protocol. The collapse of the Johnson government first, and the disastrous one of Truss later – with the simultaneous economic crisis that has since engulfed the country -facilitated the openings on both sides toward a sustainable solution for a compromise agreement. EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and outgoing Prime Minister Sunak reached a deal and signed the Windsor Framework, on February 27, 2023.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub

![La presidente della Bce, Christine Lagarde [Francoforte, 6 marzo 2025]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/lagarde-250306-120x86.png)

![Un atomo. L'Ue punta sul nucleare di nuova generazione per il suo futuro energetico [foto: iStock]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/atomo-120x86.jpeg)