Brussels – The name of Ursula von der Leyen as the future president of the European Commission—succeeding herself as the head of the Union’s executive—is gaining credence with each passing hour. The strong electoral affirmation of his European People’s Party at the polls between June 6–9, coupled with the inability of the major allies to propose a credible alternative because of the outcome of the vote, has cleared the horizon, at least in the European Parliament, of other names that could contend for her seat at the Berlaymont. Yet, while von der Leyen speaks for all intents and purposes from the pole position of the candidacy for the Commission presidency, it is from the national governments that she must watch her back, where uncertainty still reigns after the political earthquake in France and Germany. The risk of a possible paralysis of the EU institutions cannot be entirely ruled out, and the coming days and weeks will be decisive in figuring out what expectations to place on the June 27-28 European Council.

“Citizens want a Europe that delivers results; starting tomorrow, I will build a broad coalition for a strong Europe,” von der Leyen made clear today (June 10) at a joint press conference with the president of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CHU), Friedrich Merz, in Berlin: “We will build a bastion together with others against the extremes of the left and right.” The call for cooperation with the European Social Democrats and liberals—the former having emerged almost unscathed from the test of the vote, the latter considerably downsized—had come as early as yesterday evening (June 9) from the EU Parliament, commenting to the press on the projections for the 10th legislature. But from Berlin, the Commission’s number one was keen to remind that “the groups in the European Parliament have not yet been formed” and, with no certainties about either composition or final size, “to save time, I am talking to those with whom I have already cooperated well and for a long time, but this also leaves doors open.”

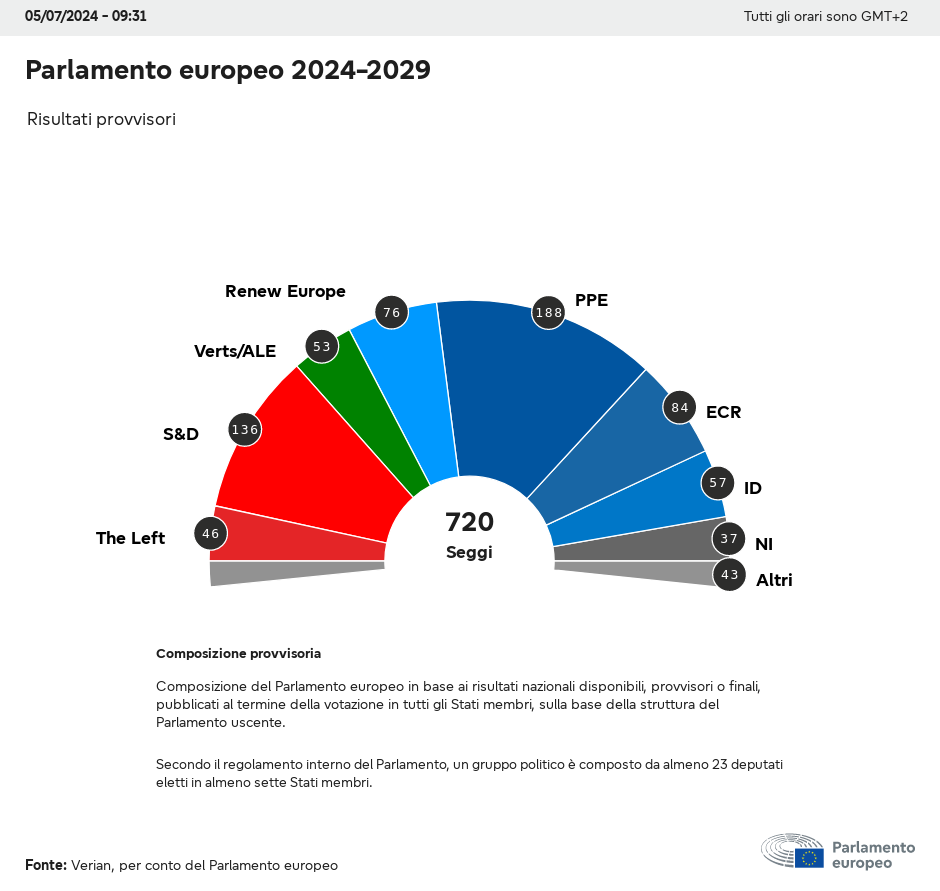

The pro-European majority holds up in the European Parliament, with the core EPP-S&D-Renew Europe still at the centre of any majority talk: “In these turbulent times, we need stability, responsibility, and continuity,” von der Leyen pointed out, reiterating that “my goal is to continue on this path with those who are pro-European, pro-Ukraine and pro-State of Law.” That leaves the door ajar for the European Greens—the real losers in these elections—who are trying to catch up by focusing on a sense of “responsibility” and going to shore up a majority that, with about 400 seats (the minimum threshold is 361), could constantly risk blackmail by free riders. But it should not be forgotten that in those three red lines, von der Leyen herself, in the election campaign, had also included the Italian Premier and President of the Party of European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), Giorgia Meloni, even though closing to an alliance with the entire conservative group. Currently, the number one in the EU executive is not uncovering her cards, and it remains difficult to think of the 24 MEPs of Fratelli d’Italia in the same majority as the Italian and non-Italian Social Democrats.

Valérie Hayer, the president of the Renew Europe group, surely won’t stand for it. Speaking to the press today in the EU Parliament, she ruled out any agreement with ECR: “It’s the group of Giorgia Meloni, of PiS in Poland, of Reconquête in France, it’s an extreme right, and we will preserve the cordon sanitaire.” A group which the Hungarians of Fidesz could also join, with the not unlikely scenario of a third-place finish in membership gained right at the expense of the European liberals (who are discussing the possible expulsion of Dutch members and the equally likely exit of Czech ones). But for Hayer, there is no doubt that “no coalition can be done without us, and we assume the responsibility to talk to pro-European and democratic forces as soon as possible,” with the goal of building a “pro-European and centrist coalition around our political group.”Von der Leyen’s name is tied to the political program because “political priorities take precedence.” Still, the current president of the Renew Europe group shows no hesitation in discussing the prospect of an encore performance by the EPP candidate (albeit conditional).

If the centre majority holds in the European Parliament, the real games will be played at the table of the heads of state and government of the 27 member countries. And this is where the situation becomes more slippery and uncertain. The decision by the French president, Emmanuel Macron, to call early elections after the hard-fought defeat of the Besoin d’Europe liberals could be the prelude to an accelerated timetable for appointing the next Commission presidency before the June 30 vote. However, it cannot be ruled out that the Elysee tenant could freeze everything until the July 7 runoff to see what the balance of power in France is: then the scenario of not only the far-right Rassemblement National in government but also a potential clash between president and prime minister over the nomination of the Commission chairmanship could be set up — and von der Leyen is openly opposed to the party of Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella.

There is also a need to consider the general weakening of the ‘traffic light’ coalition in Germany between the Social Democrats, Liberals and Greens. This is not bad news for von der Leyen and her Cdu, as a strong assertion could have jeopardized the appointment to the Commission of a politician who is part of the largest party excluded from the government. On the other hand, a strong presence from Berlin will be missing at the European Council table since the chancellor, Olaf Scholz, is now under even more domestic political pressure and concerned with the electoral assertion of the far-right Alternative für Deutschland. The table of the 27 leaders could be even more uncertain: Austria, just months before the fall elections, looks increasingly to the far right (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs is the first party with 25.7 per cent); the Netherlands are about to launch the right-wing government with the eurosceptic nationalists of the Party for Freedom; and Belgium could be without a government (potentially for months) after yesterday’s federal elections and the majority conundrum over the success of Flemish nationalists and the far right.

While the situation in the European Parliament after the elections tends to stabilize on the pro-European centre, and with the start of discussions among the parties of a possible majority (including the Greens) on the appointments of the heads of the EU institutions, von der Leyen will have to pay attention now to the balance among the 27 governments to bring home her reappointment to the Berlaymont, for this is precisely where the pole position could turn into a tailspin and the “bulwark” against extremists into a collapse of the anti-extreme right-wing dam in the EU.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub

![[foto: Emanuele Bonini]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/WhatsApp-Image-2024-06-10-at-15.22.24-350x250.jpeg)