Brussels – On the eve of the European elections (June 6-9), the European Union is ready to address threats from online disinformation. The EU wants to limit as much as possible that domestic and foreign influences threaten the vote of European citizens. It is no coincidence that many videos and content have appeared on social media that exalt abstention through false or non-contextualized information. The fight against misinformation is being fought by the European institutions throughout the year and not only under elections, although the fruits of this battle are seen in voting.

“We are prepared for the threats,” said Lutz Güllner, head of the division for strategic communications and information analysis at the European External Action Service. Güllner emphasized how his office has been analyzing and studying the member states’ elections to be ready for the June 6-9 date. “At the moment, we are in line with the expectations of disinformation; there are a number of ghost accounts on social media that aim to polarize the debate and that do not mind resorting to fake news to substantiate their theses,” Güllner said.

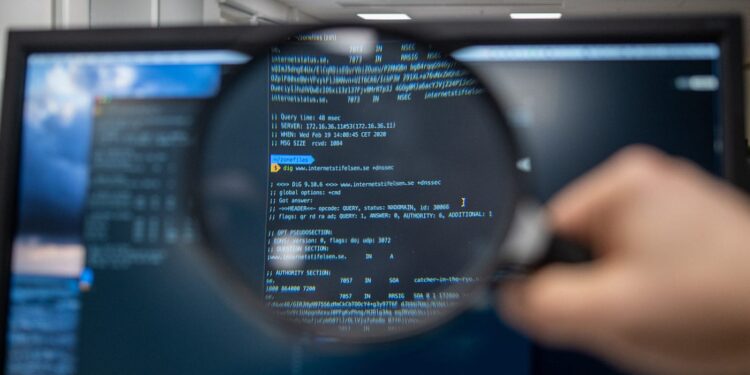

There are various methods by which well-poisoners operate, from spreading fake videos created with artificial intelligence to sharing manipulated information and even bombarding fact-checkers with fake news so that they cannot do their job. Lutz Güllner pointed out that the 72 hours before the vote are the most sensitive because many voters decide what to do in this timeframe and because it is when disinformation is concentrated. The EU has arranged a program called the Rapid Alert System, which checks and analyses online disinformation in collaboration with member states.

Of particular concern is Russia, both because it has a long tradition and experience in disinformation and because it has repeatedly attempted to influence the outcome of elections. Lutz Güllner argues that in the last period, the quantity of disinformation on the web has not increased as much as the quality: refined tactics have sprung up, such as creating websites that look like famous newspapers but actually spread fake news. None of the twenty-seven countries is safe from disinformation, but Güllner points out that the Baltic republics and large European states such as France and Germany have suffered the most attacks. Not only that, the type of misinformation is not the same but changes from country to country, as does its target audience: it may be that in the next few hours, some specific accounts (even fewer than 5,000) will display specially created messages containing fake news.

One of the disinformation videos on social media urging people not to vote.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub#astensione#iononvoto#europe2024 pic.twitter.com/h2it9F0b77

– ‘ (@Maurizio6116) June 5, 2024

![Una donna controlla le informazioni sul cibo specificate sulla confezione [foto: archivio]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Etichette-alimentari.jpg)