Brussels – “Plan A is a commitment to negotiate, and Plan B is a response,” not only targeted but also more muscular. When it comes to tariffs and reaction to U.S. policies, the key for the European Union is “a gradual response,” stresses Michał Baranowski, undersecretary for Economic Development of Poland, the country with the EU Council rotating presidency, at the end of the meeting of ministers responsible for trade convened to discuss the immediate future of trade relations with Washington. The European Union prefers “a negotiated solution that wipes out the risk of trade wars” with the case’s economic repercussions and job losses; “that’s what everyone wants,” and work will be done to that end.

In the EU strategy, between Plan A and Plan B, there is a list of targeted products to be defined by the Commission in the coming hours in order to impose—starting April 15—the first European counter-tariffs. Certain food products (soybeans, curry, turkey meat, liver sausages), certain categories of household appliances (ovens and stoves) and iconic products (Harley Davidson and pickup trucks) could end up on the European “blacklist” of “made in the USA” to be hit.

In the meantime, the Twenty-Seven bloc, in addition to showing a clear line, also succeeds in demonstrating compactness and unity. The ministers’ meeting leaves the image of a Union in the true sense of the word. The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, is the first to say what her Trade Commissioner, Maros Sefcovic, will repeat at the end of the Council’s work: The EU has proposed a reciprocal zero duty regime on cars and all industrial goods, a proposal currently rejected by Washington.

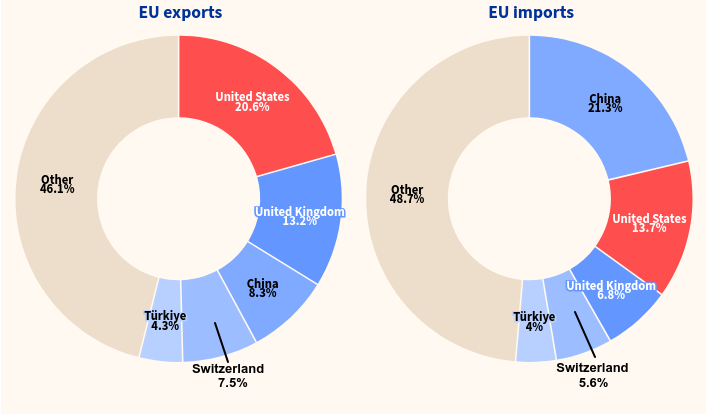

Sefcovic points out that the Commission is ready to work with the White House on an initial transatlantic free market for at least five major categories: autos, industrial and pharmaceuticals, steel and aluminium, timber, and semiconductors. However, in the idea submitted to the Trump administration as early as March 19, there are also plastics, chemicals, and machinery. On this, as on the rest, the EU is not giving up: “We are ready to negotiate as soon as the U.S. wants us to,” the trade commissioner stresses.

There is a negotiating table that is being held in parallel with the one opened in Luxembourg, and that is the one von der Leyen is running with Norway and its prime minister Jonas Gahr Støre, with whom she is discussing new cooperation that also involves a response to Donald Trump’s America’s tariffs. If there is one effect for which the EU can look positively at the trade tensions produced by the United States, it is the fact that all-new connections are being made. One of them is with Norway; the other is with China. Sefcovic and Baranowski, undersecretary for economic development of Poland, the country with the rotating presidency of the EU Council, confirm that the ministers agree with seeking new relations with China.

“We need to re-engage with the People’s Republic of China,” Sefcovic acknowledges. “It’s time to sweep some of the existing problems off the table,” he insists in what could serve as further leverage to unhinge Trump’s aggressive trade policy. Euro-Atlantic trade tensions do not eliminate existing ones with Beijing, translated into practice with the EU duties on electric car made in Asia, but they can be an opportunity for Europe to overcome them in response to U.S. restrictions.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub

![I ministri responsabili per il Commercio riuniti per discutere la risposta ai dazi di Donald Trump [Lussemburgo, 7 aprile 2025. foto: European Council]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/commercio-250407-350x250.jpg)