Brussels – The EU takes an extra step to defend itself against foreign interference. With its third annual report on threats of manipulation and disinformation from external actors, the External Action Service draws (literally) a map of the networks of malign operations set up by Russia and China, shedding light on the still-dark galaxy of dangers to European democracies.

It is hardly news that hybrid threats of all kinds are looming over the Union. The interference and information manipulation operations put in place by foreign actors (FIMI) are ending up more and more in the spotlight, especially in these times of increasingly head-on confrontation with Vladimir Putin‘s Russia, which uses cheap but effective methods to destabilise opponents.

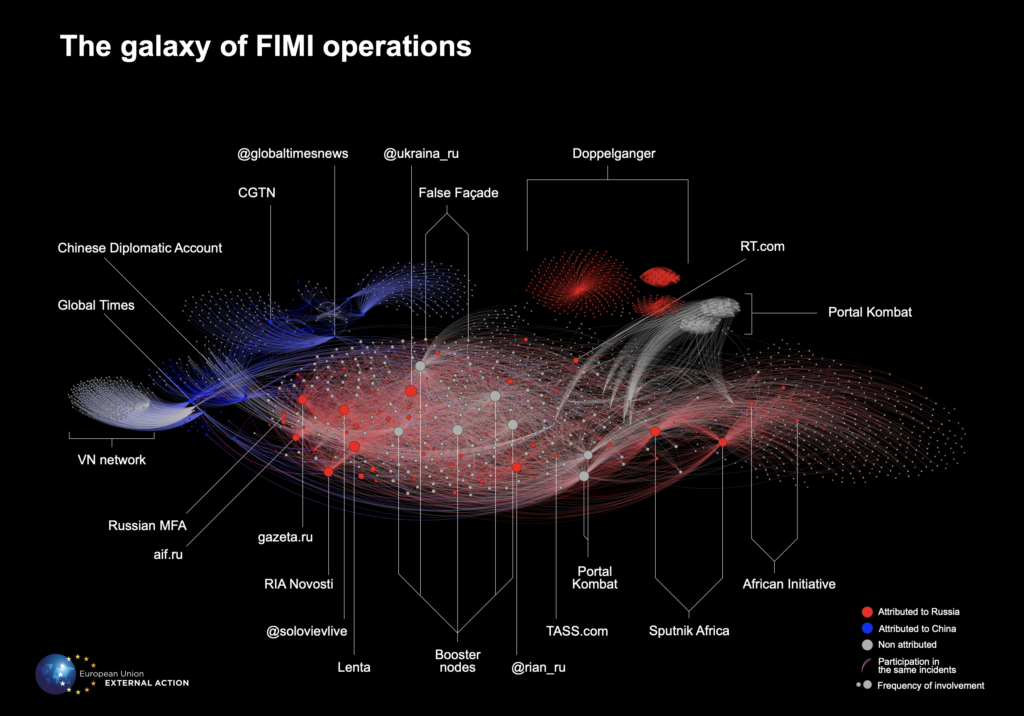

The third annual report on the subject by the European External Action Service (EEAS), published today (March 19), sheds some light on the functioning of FIMI operations in the Old Continent. The EEAS has created an “exposure matrix,” an analytical tool to counter attempts at interference and manipulation perpetrated in the Union’s information space and unveil its “complex, multilevel digital architecture.”

Investigating the interaction between online media networks (covert and otherwise) and the channels favoured by malicious actors, the matrix has revealed the vast infrastructure used by Moscow and Beijing for their FIMI activities, in which official channels and state-owned media are only the tip of the iceberg. In fact, these interact with a vast network of channels linked or affiliated with state actors in less obvious ways, making their operations more devious and their detection more difficult. Russian and Chinese operations such as Doppelganger, False Façade, Paperwall or Portal Kombat, the report argues, are different from each other but sometimes interact to undermine Western democracies.

The report examined 505 “FIMI incidents” that occurred in 2024 on some 38,000 channels in some 90 countries around the world, involving 322 organisations. About half of the attacks targeted Ukraine, but other targets included France, Germany, Moldova, and several states in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Among the main targets of operations have been election processes (e.g., 42 attempts recorded during last June’s European elections alone). Social platforms are the preferred venue for launching these campaigns (alone, X hosted 88 per cent of them), while “the main tactics, techniques, and procedures included botnets and coordinated inauthentic behaviour, as well as impersonation and the creation of inauthentic news websites.”

Speaking at a conference on the subject, High Representative Kaja Kallas emphasised that “if disinformation is a bullet that strikes democracy to the heart, FIMI operations are the gun and the whole arsenal” in the hands of actors who want to undermine the foundations of European societies by poisoning public debate and impeding citizens “to trust what they see or hear”.

FIMI operations, she cautioned, are “not a communications problem” but a strategic threat in their own right. “Our information space is nothing less than a geopolitical battleground,” she said, “and right now we are losing the war.” She reiterated that the EU invests in this dimension of its security infinitely less than Russia and China, but there are some positive signs.

The twelve-star diplomacy chief listed some actions the EU is already taking to counter the malign operations of foreign actors: exposing the networks used to conduct FIMI campaigns, as this increases costs for those running them; increasing awareness at the public level (e.g., through online databases such as the EUvsDisinfo website) as well as the capacities of state and community structures to detect threats and deal with them; and sanctioning culpable actors when they can be identified.

Finally, the EEAS report concludes that the “tireless work of civil society organisations, independent journalists and fact-checkers to uphold the integrity of information and protect fundamental freedoms in an increasingly challenging geopolitical environment also remains essential to the resilience of democratic communities.”

The two previous reports had focused on establishing the methodological framework to standardise the approach to investigations of FIMI activities and the collective countering and responding mechanisms.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub

![Un campo coltivato [foto: imagoeconomica]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/campo-coltivato-120x86.png)

![[foto: Wikimedia Commons]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/alzheimer-120x86.png)