Brussels – Next Sunday (Feb. 23), Germany will hold parliamentary elections. This is an important election not only for Europe’s leading economy but also for the entire EU and Old Continent, including Ukraine. In the coming days, we will publish an update on the polls and trends of the various parties on the eve of the vote. Here, we offer an overview of the main issues of the public debate and the election campaign to understand what Germans are worried about and what will motivate them to go to the polls.

Migration and Security

In recent months, the issue of immigration has sprung to the top of voters’ thoughts. After a series of deadly terrorist attacks (three since last December, in Magdeburg, Aschaffenburg, and Munich), many political actors have made it a security issue. On this issue, the positions of all parties have stiffened.

The Christian Union Democrats—consisting of the CDU, led by Friedrich Merz, and its Bavarian sister party, the CSU of Markus Söder—want a tightening of illegal immigration that also passes through a tightening of asylum policy and the strengthening of national border controls. They have attempted to

make the Bundestag approve

a series of restrictive measures on the issue by playing hand in hand with the ultra-right AfD but ultimately failed. The Union favours expanding the video surveillance network in public spaces and introducing facial recognition systems (e.g., in stations and airports).

The Social Democrats of the SPD, the party of outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz, have promised to accelerate asylum procedures for refugees, to work on comprehensive agreements to incentivise economic immigration and facilitate the repatriations of those who do not qualify for international protection in Germany.

The Greens have a similar position. On the one hand, environmentalists pledge to defend the right to asylum and to honour Berlin’s commitments under EU and international law. On the other hand, they oppose repatriations to war or crisis zones, just as they oppose the externalisation of asylum procedures in non-EU countries (as attempted by Italy with the CPRs in Albania).

For the nativist and xenophobic right-wing AfD, led by Alice Weidel and Tino Chrupalla, permanent controls at German borders should be re-introduced (in open contravention of Schengen rules) and legalised refoulements (in violation of international law). Regarding security, it favours preventive detention but opposes extensive video surveillance in public places.

The liberal-conservatives of the FDP oppose surveillance in public places as well as online and on social platforms, while agreeing with a clampdown on illegal immigration.

The radical left Die Linke proposes a deep reform of state management of migration flows, creating among other things a dedicated ministry. Liberalization of visa policy, funding for “welcoming” municipalities, revision of the citizenship law (including the introduction of ius soli), stopping repatriations, and legalizing irregular migrants are some of the proposals on migration.

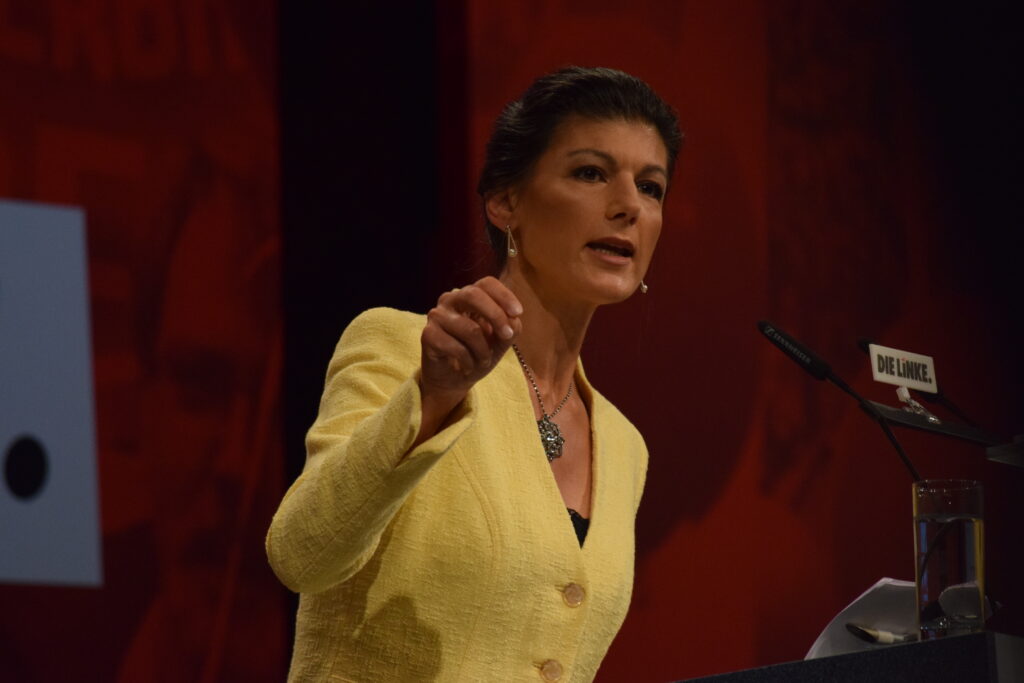

The red-browns of the BSW, the alliance led by Sahra Wagenknecht (rising star of Germany’s so-called “conservative left”, who came right out of the Linke), instead adopt a more chauvinist stance, not far from that of the AfD.

Economy and cost of living

The other major campaign theme is the state (rapidly deteriorating) of the national economy, which has been in recession for more than two years. Businesses are on the warpath, demanding tax cuts and a reduction in both energy and bureaucratic costs, while unemployment is rising in the country and foreign investment is falling.

Germany’s trade model, which had ensured its solid success over the past decades, was based on imports of cheap raw materials and energy and exports of valuable products processed by industry, on which about a quarter of GDP depends. However, the economic downturns of recent years (from the suspension of international trade during COVID-19 to the energy crisis and the inflationary spiral that followed the war in Ukraine) have made the system unsustainable. Exacerbating the situation are the trade tariffs that Donald Trump is threatening.

All of this has resulted in a generalised rise in the cost of living, from which the young generation, in particular, is suffering. In fact, they are abandoning traditional parties and paying renewed attention to formations perceived as anti-system, starting with the AfD and the Linke.

The backbone of Germany’s economic strength, the automotive industry, has been in the dump for some time (like the entire automotive sector on the Old Continent). After historically being the driver of growth, it is now dragging the entire country into the precipice as Chinese competition floods the European market with good-quality electric vehicles with incomparably lower production costs thanks to generous government subsidies.

On the contrary, German companies have had to bear intensive costs for electrification in recent years. This is why many of them are opposed to the dreaded backtrack on the stop to the endothermic engine in 2035 (wanted by the CDU/CSU, the AfD, and the BSW but opposed by the SPD, Greens, and Left), as it would blow up their medium to long-term planning.

Merz is intent on breaking dependence on the People’s Republic by, among other things, discouraging German automakers from investing and relocating to the Asian country (ruling out new bailouts with public money). At the same time, the CDU wants to lower corporate taxes and reduce energy costs. Among the SPD’s proposals is a new phase of public investment, including in traditionally industrial rural areas.

Public Finance

One of the most thankless tasks for the new German government will be to close the approximately €25 billion budget hole in the state coffers, the source of the collapse of Scholz’s “traffic light coalition” that left Germany without a budget for the current year.

The problem is that the German constitution enshrines the principle of fiscal parity, which effectively imposes a ceiling on Berlin’s debt annually, setting the borrowing limit at 0.35 per cent of GDP (barring emergencies). However, with soaring defence spending and green and digital transitions, tax revenues are no longer enough to cover spending.

The Union and the FDP regard the sacredness of curbing public debt as inviolable. Merz aims to reduce subsidies and bureaucracy while reviewing social spending by reducing the income tax. He does not talk about cutting pensions but envisions an incentive plan for those who wish to continue working beyond retirement age. However, according to various estimates, even these proposals would cost at least 90 billion.

In contrast, SPD and Grünen are pushing for a reform of constitutional provisions to “modernise” state spending rules. In an unprecedented historical twist, the reform of budget constraints would even appear to be supported by an absolute majority of German voters.

The Social Democrats are not intent on reforming the pension system, but they would like to increase the minimum wage and introduce a capital levy for the super-rich, as would the Greens. Environmentalists propose new subsidies for electric cars and a “citizens’ fund” to guarantee pensions. Taxes for the wealthiest segment of the population are also a workhorse for the Linke, which is also calling for an inheritance tax on large inheritances in addition to increases in minimum wages and pensions.

For Scholz, forcing a 60 percent cap on GDP is counterproductive, given that all G7 economies already exceed 100 percent. The chancellor also opened the door to revising EU budget constraints, supporting the uncoupling of defence investment from calculating the deficit/GDP ratio to move closer to the NATO spending targets (currently at 2 per cent but targeted to increase in the near future).

The FDP, like the CDU, calls for a revision of the pension system, a relief of the tax burden on businesses and a reduction of the bureaucratic structure. Social spending, they say, should be redirected from employment subsidies toward incentives to hire. As for social security, the AfD is pushing for foreign nationals to be eligible only after working in Germany for a minimum of 10 years.

Ukraine and defense

German public finances have also been put under pressure by the increased defence spending, a hallmark of this historical phase. Shortly after the Russian invasion in February 2022, the Bundestag approved the introduction of a special 100 billion fund (financed by borrowing) to modernise the German military (Bundeswehr), and from which to also draw to provide military aid to Ukraine.

In 2024, the massive fund injected 20 billion into the defence budget, boosting it to about 72 billion (a figure that rises to over 90 billion if aid for Kyiv is also counted). In this way, Berlin hit the target of 2 per cent decided by the alliance for the first time, but maintaining it would require nearly 30 billion additional per year.

Bringing defence spending to an even higher percentage of GDP (with annual investments in the order of 80 billion) is a goal of the CDU/CSU, which says it is in favour of continuing support for Ukraine. Indeed, increasing military spending and maintaining support for Kyiv’s resistance are commonalities with the SPD and Greens. The leading candidate of the Grünen, outgoing vice-chancellor Robert Habeck, says he wants to allocate 3.5 per cent of GDP to defence, raising the necessary resources through borrowing. On the front of the “no” side of sending arms to the former Soviet republic, however, are the Linke, the AfD and the BSW.

External Relations

While most German political forces do not question Germany’s Euro-Atlantic collocation (net of President Trump’s unpredictability), several criticisms come from opposite ends of the spectrum. The AfD would like to abandon the EU and the single currency, while the Linke and the BSW are deeply critical of Berlin’s role in NATO. The far-right of Weidel and Chrupalla pushes for a rapprochement with Moscow and the abandonment of sanctions, as do the red-browns of Wagenknecht. All three of these formations share a platform of marked anti-Americanism.

The Union remains pro-Israel (while declaring itself in favour of a two-state solution) while framing relationships with Beijing within a “systemic competition“ framework: maintaining close economic ties but reducing strategic dependencies. The SPD also claims a similar approach to China.

Climate and environment

Ecological transition has become a rather controversial issue in Germany. On the one hand, the measures taken by the outgoing government (most notably the regulations on heat pumps, which Habeck himself wanted) have provoked a strong public reaction, both from businesses and from the less protected segments of the population.

On the other hand, the need to respond to Russia’s aggression on Ukraine (especially after the Constitutional Court opened a 60 billion hole in the state budget) has caused climate goals to drop down the priority ladder. The Grünen themselves have lowered their sights from the maximalist demands with which they had brought home an excellent result in the 2021 elections.

Merz calls wind turbines a “thorn in the flesh,” while the CDU/CSU is banking on nuclear power even though research has stalled for decades. Electricity production from renewables (solar and wind) accounted for over half of the total in 2024. Germany’s last atomic plant was decommissioned in 2023 under decisions made by the last Christian Democratic chancellor, Angela Merkel. The Union plans do not include reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 65 per cent by 2030.

Scholz has also advocated increasing the import of oil and LNG from the United States to bring down soaring energy costs. For its part, the AfD denies human causation of climate change, supports the creation of new coal-fired and nuclear power plants, and aims to resume imports of Russian natural gas.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub

![La conferenza stampa tenuta al termine del vertice informale dei leader Ue per discutere di difesa [Bruxelles, 3 febbraio 2025]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/euco-250203-350x250.png)