Brussels – It doesn’t take much for the dust swept under the carpet to be lifted. A series of close tragedies, straddling the start of the new year, remind us that the Central Mediterranean migrant route is still the deadliest and that despite the sharp drop in landings claimed by Rome in Brussels as a significant success in the fight against smugglers and traffickers the Mare nostrum continues to be a vast graveyard. Even in 2024, more than 2,000 migrants died or went missing trying to reach the shores of the EU. Most of them on the route from the Tunisian and Libyan seashores to the Italian seas.

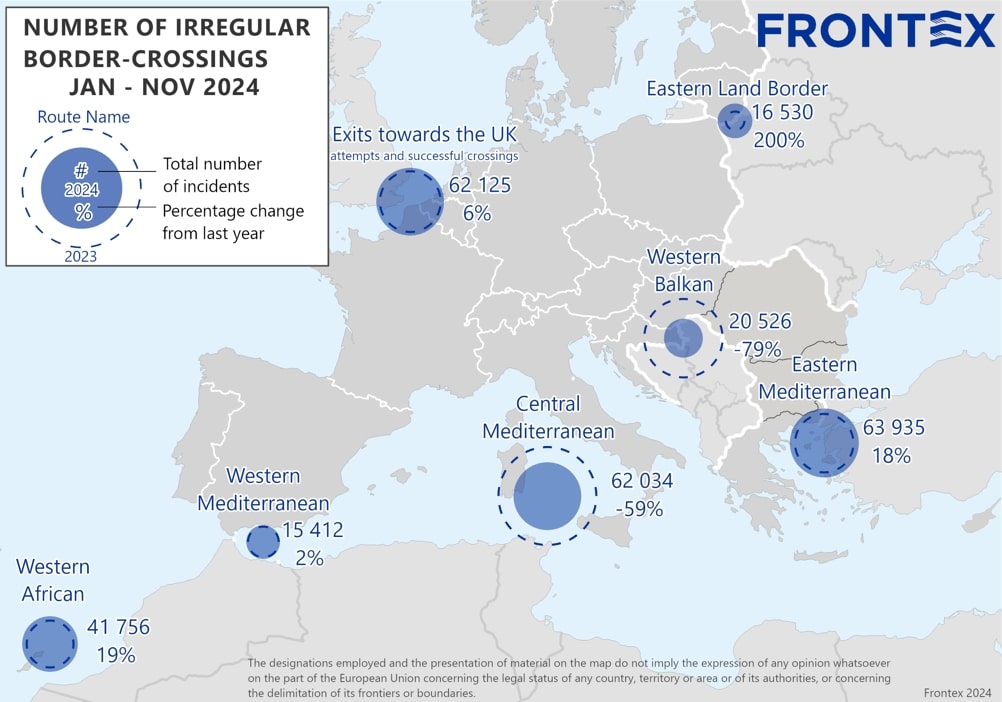

While in 2024, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) certified a reduction of 59 per cent more irregular arrivals from the central Mediterranean than in the previous year, data collected by the Missing Migrants Project International Organization for Migration (IOM) tell of a rising death rate. Sixty-two thousand irregular entries are matched by 1,695 deaths or missing persons. For every one hundred migrants who made it, nearly three never arrived. Considering also the eastern and western Mediterranean routes, in 2024, IOM documented 2,279 people dead or missing on the journey to Europe.

In the last ten years, that’s 31,184. The peak was in 2016, when, according to the Missing Migrants Project, there were 5,136 victims in the Mediterranean. In recent years, the number of dead and missing has stabilized: 2,048 in 2021, 2,411 in 2022, 3,155 in 2023, and 2,279 in the year just ended. Among them, 112 minors.

The latter figure was the starting point for the denunciation of UNICEF Special Coordinator for Refugee and Migrant Response in Europe, Regina De Dominicis, who, in a statement, pointed out that among the 2,200 migrants who died at sea in 2024 “there are hundreds of children, who make up one in five of all people migrating across the Mediterranean,” of whom “most are fleeing violent conflict and poverty.” De Dominicis recalled the shipwreck not far from the shores of Lampedusa on New Year’s Eve, which left more than 20 people missing, including five women and three children, and only seven survivors. A tragedy that came “only weeks after another fatal accident off the island left an 11-year-old girl as the only survivor.”

In these early hours of 2025, two makeshift boats bound for Europe sank off the coast of Tunisia. Three miles off the coast of El Attaya, in Kerkennah, 83 migrants were rescued, along with the bodies of 27 fellow travellers, including women and children. At the same time, northeast of Djerba, in international waters, another boat with 60 people on board sank.

UNICEF called on the governments of the 27 EU countries “to use the Pact on Migration and Asylum to prioritise the safeguarding of children,” with an emphasis on “ensuring safe and legal pathways to protection and family reunification, as well as coordinated search and rescue operations, safe landings, reception in communities, and access to asylum services.”

But the focus—in Brussels, as well as in Rome and most European capitals—is increasingly oriented on the security dimension of the migration phenomenon, on reducing departures, as evidenced by the agreements that the European Commission signed last year with countries of origin and transit on the African continent: Tunisia, Mauritania, and Egypt above all. The idea is that, in addition to increasingly limiting the entry of migrants into member countries, fewer departures necessarily correspond to fewer victims. However, coordinated search and rescue operations are not even discussed. On the contrary, those who do are increasingly forced to give up, as happened to Doctors Without Borders and its search and rescue ship, the Geo Barents, which last December 12 announced the end of operations in the central Mediterranean “because of absurd and senseless laws”.

In a harsh statement, coordinator Margot Bernard accused Italian authorities of “undermining the operations” of humanitarian ships. According to MSF, “Italian laws and policies express a real disregard for the lives of people crossing the Mediterranean.” The hard line against migrants affirmed in Italy under Giorgia Meloni’s government is the thread that ties the Italian premier to the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, who has so far always supported Rome’s initiatives. And even the new European Commissioner for Home Affairs and Migration, Austrian Magnus Brunner, has not uttered a word on the recent shipwrecks. “When European deterrence policies cause so much suffering and cost so many lives, we have a duty to insist on behalf of humanity,” MSF closed by announcing the halt to operations of the Geo Barents. A ship that, as of June 2021, had performed over 190 rescue operations and rescued over 12,675 people.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub