Brussels – It is a historic first, which “aims to immediately put on an equal footing with the member states the four EU accession candidate countries that have already begun negotiations with Brussels.” In the Rule of Law Report 2024 published today (July 24) by the European Commission, Albania, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia also make an entry, with four specific chapters for the most advanced of the ten countries involved in the EU enlargement process. What the EU executive itself calls “the main new feature” of the annual rule of law report, now in its fifth edition, will, together with the EU Enlargement Package recommendations, form the basis for “supporting their reform efforts, helping the authorities to make further progress in the accession process, and preparing to continue work on the rule of law as future member states.”

In Brussels’ vision, respect for the rule of law and EU enlargement go hand in hand, as “a key objective of EU enlargement is to firmly entrench the rule of law on our continent.” Hence, the decision to extend the assessment of the progress and shortcomings framework on this “core element” of the Union’s scaffolding—usually reserved for the Twenty-Seven—also to four countries that have already begun accession negotiations. The momentary exclusion of Ukraine and Moldova is because they have been joining for too short a time (exactly one month). At the same time, Turkey has already been analyzed separately in November last year for its total stalemate since 2018.

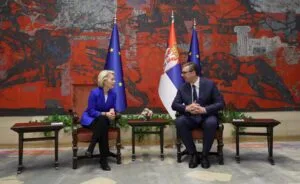

The von der Leyen cabinet’s overall analysis of the rule of law framework in Albania, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia starts with the “particularly worrying” scenario of “attempts to interfere by Russia, with disinformation, anti-democratic, and anti-EU rhetoric,” particularly after the start of the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. However, there is more, namely the need for “credible and sustainable reforms to progress toward EU membership” by these candidate countries, also to access substantial funding from the Western Balkans Reform and Growth Instrument and Ukraine facility. “Based on objective and merit-based criteria,” the new approach adopted by the Commission may be “extended in the future to other EU enlargement countries” (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kosovo, Moldova, Turkey, and Ukraine), not only “to achieve irreversible progress on democracy and the rule of law prior to accession,” but also “to ensure high and lasting standards after accession.”

The Rule of Law in Albania

The analysis of the rule of law in Albania starts with the issue of the “substantive” judicial reform implemented since 2016. Although “scrutiny of all judges and prosecutors has strengthened accountability,” the Commission notes “shortcomings in the appointments of non-magistrate members of the Supreme Judicial and Prosecutorial Councils,” but especially “concerns” over “limited transparency and difficulties in ensuring timely and qualitative evaluations” in the process of appointing, promoting, and transferring magistrates, as well as “attempts to interfere with and pressure the judiciary by public officials or politicians.” Significant challenges stem from the financial and human resources shortage, which “negatively affects” the quality of justice and the “lengthy and large backlog” of judicial proceedings.

The initial results of the Special Anti-Corruption Structure (SPAK) are “encouraging”, but the authorities specializing in repression and prevention “report shortcomings in specialized resources and available tools,” while the number of people investigated, prosecuted, and convicted for corruption

offences “has increased over the last three years.” Since corruption “is prevalent in many areas, including during election campaigns” and the “overly complex” legal framework limits preventive measures, Brussels points the finger at the recent amnesty law and the lack of coordination between national authorities. Also mentioned are the “deep” political polarization, which has “a negative impact on the effectiveness, transparency, and objectivity of parliamentary work,” and the“challenging environment” for civil society organizations, “including in relation to registration requirements and limited public funding.”

Among the major elements of concern for respect for the rule of law in Albania are those related to the area of media freedom, most notably those on the independence of the public broadcaster, “limited regulation on transparency of media ownership and high concentration,” and the failure to ensure “fair allocation of state advertising and other state resources.” Although the framework for protecting journalists is already in place, “Verbal and physical attacks, smear campaigns and strategic lawsuits against public participation against journalists are a cause for concern.“

The Rule of Law in North Macedonia

North Macedonia “has undergone several waves of judicial reforms,” but the independence of the judiciary and the institutional ability to protect it from undue influence “remain a serious concern,” and the perceived level of judicial independence “is very low”. Appointment decisions of prosecutors and judges “have been criticized by civil society because they are not comprehensively justified or based on objective criteria,” the “limited” resources allocated “may affect financial autonomy.” The deficit in human resources “could impact the quality and efficiency of justice,” as evidenced by the fact that “the efficiency of the judiciary has declined for first instance civil, commercial and criminal cases”.

Although there is a national anti-corruption strategy, “its implementation lags behind,” warns the Commission: “The risk remains high in many areas,” and recent amendments to the Criminal Code “have weakened the legal framework, negatively affecting the prosecution of corruption,” especially in high-level cases. Among the most critical issues are “scarcity of resources and lack of cooperation between national authorities,” gaps in political party financing, and “no registered lobbyists” on official special lists.

The political polarisation in the national parliament remains central and “has caused delays in its work and led to excessive and sometimes inappropriate use of expedited legislative procedures,” even though civil society organizations can operate in an “overall favourable” environment. In this regard, legislative measures “have enhanced legal safeguards” for the protection of journalists, “yet threats and acts of violence against journalists have been noted.” The Council on Media Ethics “continues to be put under pressure” and challenges persist on transparency of media ownership, with “concerns about some elements of the reintroduction of state-funded advertising.”

The Rule of Law in Montenegro

As for Montenegro, the most advanced country on the road to EU accession, “it is going through an intense reform phase, including the adoption and revision of a comprehensive package of laws” on the independence, accountability, and impartiality of the judiciary and the prosecution, including a new judicial reform strategy 2024–2027. The significant delays in high-level judicial appointments staged between 2022 and early 2023 have had an impact on the system in general but “by now only a new President of the Supreme Court remains to be appointed,” and “serious challenges exist regarding the efficiency of justice, where the length of proceedings for administrative cases has further increased.”

Within the 2024–2028 anti-corruption strategy, Montenegro “criminalizes most forms of corruption,” and the track record of investigations and prosecutions in high-level cases “is stable.” However, “the lack of trials and final decisions contributes to a perception of impunity.” While many institutions have specific codes of conduct, the government’s code of conduct “is ineffective” and awaits the adoption of Law on Government with disciplinary penalties. While the adoption of new lobbying legislation last June 6 is positive, less so is that the legal framework governing political party financing “is hampered by shortcomings in its scope, clarity and implementation.”

The chapter on pluralism and media freedom is thorough, with the ad hoc legislative package consisting of amendments to the National Public Broadcaster Law, a new Audiovisual Media Services Law, and a media law that “introduces improvements on transparency of ownership and other systemic areas, aiming to align it with the EU acquis.” The new legislation grants new powers to the Audiovisual Media Services Agency, “addressing the long-standing issue of its effectiveness in enforcing the regulatory framework by equipping it with comprehensive sanctioning instruments,” the EU Commission notes. However, it cannot be forgotten that “limited” information on public sector payments and institutional advertising is available. In cases of violence against journalists, Montenegrin authorities “provide effective responses” at the institutional and law enforcement level, “but there

was no effective judicial follow-up of emblematic past cases”

The Rule of Law in Serbia

The Rule of Law 2024 report ends with the chapter on Serbia. “The implementation of the constitutional reform to strengthen judicial independence is ongoing,” stresses the Commission, which notes that “political pressures on the judiciary and the prosecution remain high.” The Balkan country still lacks a comprehensive court management system linking cases between courts and prosecutors’ offices. At the same time, “efficiency shows a positive trend for civil, commercial and criminal cases, but there are serious difficulties in handling administrative cases and constitutional complaints.” Parliament’s ability to ensure the exercise of necessary checks and balances “is constrained by issues of effectiveness, autonomy and transparency, including in terms of oversight of the executive and legislative process.”

Adoption of the National Anti-Corruption Strategy 2023-2028 “is still pending,” and the current legal framework is broadly in place; however, “shortcomings exist in practice”. Although most forms of corruption are considered criminal offences, “further improvement is needed to establish a robust track record on investigations, indictments and final convictions in high-level corruption cases,” also given the shortcomings in the verification and enforcement of asset declarations and political party financing. Lobbying legislation “is limited in scope,” whistleblower protection legislation “is not yet aligned” with the EU acquis, and public procurement is a “high risk” area for corruption. Civil society organizations “lack an enabling environment for their establishment, operations and financing,” the Commission warns, opening one of the most sensitive chapters for respect for the rule of law in Serbia.

The Electronic Media Regulatory Authority “fails to fully exercise its mandate to safeguard pluralism and professional standards, and there are also serious concerns about its independence.” The measures for addressing transparency in ownership structures and in advertising

from state resources proposed in the media strategy “have yet to be fully implemented,” and, “against the background of complaints about biased reporting,” the editorial autonomy and pluralism of the public service remains critical. This is compounded by the fact that journalists continue to face “frequent refusals by public bodies to disclose information of public importance or no response at all,” and their safety “is a source of concern, as is the increasing pressure from abusive lawsuits.” In this regard, responding to questions from the press about respect for the rule of law in Serbia, the EU Commissioner for Values and Transparency, Vera Jourová, made it clear that “we will follow the situation in Serbia very closely,” and the Commission will not tolerate “attacks, threats, or intimidation by politicians who brand journalists as public threats.”