Brussels – This time, it is a triumph for the ruling party in Serbia, the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), closely controlled by the President of the Republic, Aleksandar Vučić. After a wave of protests and objections from the international community over several critical issues that arose in the conduct of December 17, 2023, legislative and local elections, the capital Belgrade was back to the ballot yesterday (June 2) for the new composition of the City Council. However, from the overwhelming victory of the party that has been in power for 12 years nationwide (and 11 in the capital), new possible irregularities and violence still emerged, as well as a now exacerbated nationalist rhetoric.

“We deplore the threats and attacks suffered by journalists while reporting on the June 2 elections,” is the complaint of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) on what happened yesterday in Belgrade: “Journalists have a crucial role in covering the elections, in informing the public about the candidates, their platforms, and ongoing developments.” The OSCE, which had already denounced a whole series of weaknesses in the conduct of the last round of voting at the national and local levels, continues to urge “political leaders, public officials, and authorities to unequivocally condemn and promptly investigate all cases of violence and threats against journalists.”

Against this backdrop, the Serbian Progressive Party, according to the final results of the vote count, won 64 out of 110 seats on the Belgrade City Council, and now former water polo player Aleksandar Šapić is poised to become mayor. Unlike in the December elections, the opposition ran divided, with some movements deciding to boycott the vote—voter turnout stood at 46 per cent—while others sided either with candidate Savo Manojlović (for the coalition “I am Belgrade too”) or with Dobrica Veselinović (for “Let’s Choose Belgrade”). Also pushing Vučić’s party to the polls was the flurry of ultranationalist rhetoric unleashed in the country after the vote at the United Nations General Assembly about the establishment of the International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the Srebrenica Genocide, which the Serbian President himself leveraged to compact the ruling party’s voter base.

The tensions between the EU and Serbia after the December elections

The six months between the December 17, 2023, early parliamentary elections and yesterday’s rerun of local elections in the capital, Belgrade, have been anything but peaceful between Brussels and Belgrade, given what happened at the polls at the end of last year. In the face of fraud and numerous illegal actions at the ballot box, thousands of people had been taking to the streets for weeks, responding to the call of the parties and movements gathered in the coalition ‘Serbia against Violence’, which had just been defeated by the Serbian Progressive Party. The OSCE-led election observation mission also detected “the misuse of public resources, lack of separation between official functions and campaign activities, as well as intimidation and pressure on voters, including cases of vote buying,” cornering the government to at least repeat the vote in the capital.

It is precisely the issue of meeting democratic standards that has exacerbated relations between Vučić’s Serbia and the EU institutions. On the occasion of the December 17 elections, MEP and member of the OSCE parliamentary delegation Viola von Cramon-Taubadel (Greens/Ale) confirmed that she had “witnessed cases of organized transportation of voters from Republika Srpska [the Serb-majority entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina, ed.]” to Belgrade without being formally registered as residents. Hence, the European Parliament required the EU Commission to take heavy actions should the authorities’ involvement in election fraud be established, including the “suspension of EU funding on the basis of serious violations of the rule of law” and, by implication, a possible halt to accession negotiations. Outgoing PM Brnabić then closed the door to an international investigation “because it would require the nullification of national sovereignty.” Still, major concerns remain in Brussels about irregularities at the polls and the lack of complete transparency in the election process.

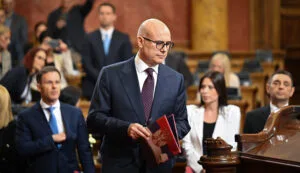

While immobility reigns in the EU Council (dictated mainly by the veto power of the Hungarian PM, Viktor Orbán, on any action against ally Vučić), in Belgrade on May 2, the new government took office, led by Miloš Vučević, a close ally of the President of the Republic as well as the leader of the Serbian Progressive Party after Vučić himself resigned last year. The new executive has placed itself in perfect continuity with the previous one (ex-premier Brnabić is now speaker of the National Assembly) in foreign policy—both on the road to EU membership and in maintaining relations with Russia and China—but also in matters considered to be domestic policy (i.e., the relationship with Kosovo, whose independence has never been recognized since 2008). Two particularly controversial figures appear among Vučević’s cabinet members, so much so that they were included in the list of people sanctioned by the US in the past year: the former head of Serbian intelligence, Aleksandar Vulin, and the longtime politician and owner of Russia-based companies Nenad Popović.

Finally, the violence case suffered by the leader of the opposition Republican Party, Nikola Sandulović, who was picked up by Serbian intelligence services on January 3 and severely beaten while in detention for paying homage at the grave of Adem Jashari, one of the founders of the Kosovo Liberation Army (Uçk). Members of the Serbian Security Information Agency (BIA) allegedly abducted and tortured Sandulović, who was then detained in Belgrade’s central prison without access to independent medical care. Among those responsible for the violence there would also have been Milan Radoičić, deputy head of Lista Srpska (the main party representing the Serb minority in Kosovo and closely controlled by President Vučić), who, among other things, has already admitted to organizing the armed attack in northern Kosovo in late September last year. The former head of Serbian intelligence, Vulin—now a member of the new government—had reportedly personally ordered Sandulović’s arrest, but the defence lawyer pointed the finger at President Vučić.

Find more insights on the Balkan region in the newsletter BarBalcani hosted by Eunews

English version by the Translation Service of Withub