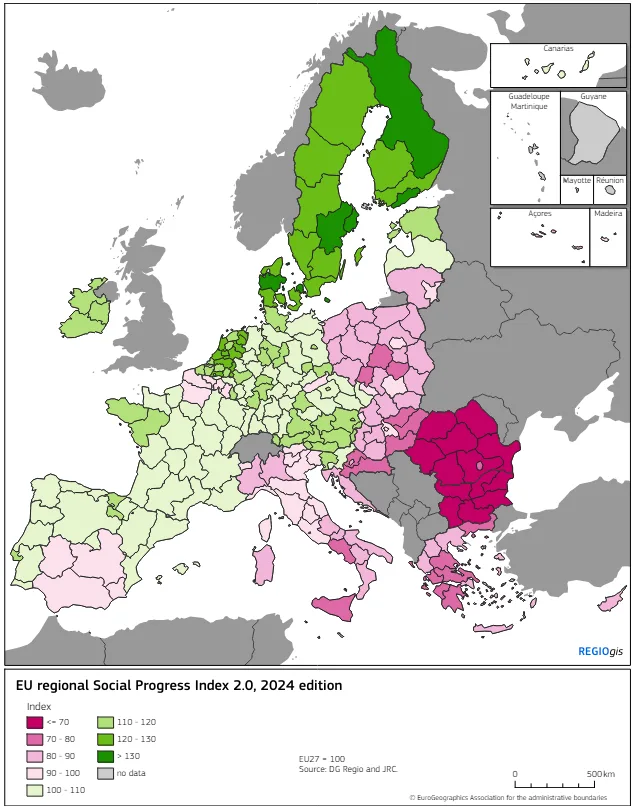

Brussels – The EU’s Regional Social Progress Index, presented today (May 23) by the Commissioner for Cohesion and Reform, Elisa Ferreira, captures a Europe split in two. This is nothing new: on the one hand, the northern regions, with Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland, and Sweden scoring high, and on the other, the former Soviet bloc and the countries bordering the Mediterranean, constantly lagging. Outrageous is the result of Campania and Sicily, ranked, respectively, 207th and 214th out of 236 European regions.

“We have long said that GDP is a useful tool for assessing the progress of EU regions, but it does not provide the full picture,” Ferreira said. “The Social Progress Index gives us a complete picture of regional development in Europe. A picture that is a judgment for Italy: looking at national averages, Italian regions are only more developed than those of Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Lithuania, Romania, and Slovakia.

To draw up the index, the European Commission took into account 53 socio-economic and environmental indicators divided into three main macro-dimensions: basic needs, foundations of well-being, and opportunities. At the European level, the survey found that about 60 per cent of EU citizens live in regions that exceed the average social progress score. However, this percentage drops to 50 per cent when focusing only on basic needs, such as health care, sanitation, and housing. Still, in less developed regions, more than 80 per cent of residents live in areas below the EU average for social progress in all dimensions, including the overall index.

The EU’s five regions leading social progress are Helsinki-Uusima and Pohjois- ja Itä-Suomi in Finland, Midtjylland and Hovedstaden in Denmark, and Stockholm in Sweden. Rounding out the ranking are three Bulgarian regions (Severoiztochen, Severozapaden, and Yugoiztochen) and two Romanian regions (South-Muntenia and Northeast). Another interesting finding is that in most member states, the capital regions performed at or above their national averages, except for those in Belgium, Greece, Spain, France, and Italy.

The all-Italian ranking is led by the two autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano, respectively 139th and 151st in Europe, while the worst are precisely Campania and Sicily. But the picture is, if possible, even more dramatic if one considers only the size of the opportunities that regions offer their citizens: at that point, in addition to Sicily and Campania, Puglia, Basilicata, and Calabria also fall into the lowest bracket, scoring in line with several regions in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Croatia and Slovakia.

To go even deeper, the Opportunity dimension is further divided into four categories: Trust in Institutions, Freedom of Choice, Social Inclusiveness, and Advanced Education. According to the latter, the “bad” includes almost all Italian regions except Lazio and, partially, the Autonomous Province of Trento. If the education of the youngest is the engine of social progress, Italy is a cat biting its tail.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub

![La commissaria per la Coesione, Elisa Ferreira [Bruxelles, 26 marzo 2024]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ferreira-350x250.png.webp)