The twin assignment that European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen has given two Italians — Mario Draghi on the issue of competitiveness and strategic autonomy and Enrico Letta on the single market. — is a unique opportunity to open a serious reflection and a debate in Europe on the future of the Union and what has not worked in the past 20 years.

The (negative) differential in growth and development compared to the other major economic areas worldwide, particularly the US, is striking. It is just as noteworthy how Europe lags for technological innovation and the importance of businesses, which are the protagonists of growth and development: There is not a single European company among the world’s top 10.

Draghi will not deliver his report until after the European elections in June, but he has already provided some glimpses and some indications in his recent speech at La Hulpe (Brussels). On the other hand, Enrico Letta has filed a meaty 147-page report with the significant title “Much more than a market.” So far, Letta’s document, as well as Draghi’s speech with its anticipations, has mostly been covered by the Italian press. There was little attention to this in Europe, showing how it will not be easy to open a discussion on these issues in Europe.

Increasing competitiveness, strategic autonomy, and defending and strengthening the single market imply fundamental political choices. In particular, it will require a radical change in the Union’s governance. It will be very complicated to implement the profound changes Draghi and Letta are talking about if the decision-making process remains as it is today — super-complex — with even the smallest of Union countries having veto rights and with excessive regulatory bureaucratism.

The issues of competitiveness, strategic autonomy, and the single market are closely linked.

Restoring competitiveness to the European industrial system means, among other things, making huge investments in innovation and in the energy and digital transitions that, so far, have been far less implemented compared with our global competitors. Making these investments necessarily involves public resources because private individuals alone cannot afford them. These indispensable public finance interventions cannot be left to individual states through the instrument of state aid, as they could create serious competitive asymmetries: in this hypothesis, the economically and fiscally stronger states will give much more to their companies than the weaker states, thereby creating large imbalances and differences in the ability of companies to meet the challenges of today.

This is what occurred in 2021-2022, thanks in part to the easing of state aid rules due to the pandemic: out of more than 760 billion euros of aid to industrial companies notified to and authorized by the Commission by member states, more than 53 percent went to German companies, about 27 percent to French companies, and only 6.5 percent to Italian companies.

Here is the link between competitiveness and the single market.

Averting competitive asymmetries capable of undermining the single market means limiting the ability of individual states to intervene on behalf of their businesses. Will countries, especially the larger and economically stronger ones, agree?

The solution is European and not national, obviously, probably debt-financed and available to all European companies in the same situation, and not just those in the strongest countries.

Would the Nordic countries accept a common debt made to support companies in other countries since industrial enterprises are scarce in their parts? There is a serious risk that the conflicts of interest internal to the Union and often silenced by pro-European rhetoric will re-emerge.

The topic of conflicts of interest brings us to the other, related topic of rules to protect competition. In this regard, Draghi rightly said that for too many years Europe has had the wrong perspective.

“We have turned inwards, seeing our competitors among ourselves, even in sectors like defense and energy where we have profound common interests. At the same time, we have not looked outward enough … we did not pay enough attention to our external competitiveness as a serious policy question. … we trusted the global level playing field and the rules-based international order, expecting that others would do the same. But now the world is changing rapidly and it has caught us by surprise. Other regions are no longer playing by the rules and are actively devising policies to enhance their competitive position…At worst, they (these policies) are designed to make us permanently dependent on them… China, for example, is aiming to capture and internalize all parts of the supply chain in green and advanced technologies. This rapid supply expansion is leading to significant overcapacity in multiple sectors and threatening to undercut our industries….”

Draghi’s reflection leads to the size of companies, the economies of scale that can or cannot be achieved in Europe in pursuit of the best efficiency, and their target markets.

Until now, the European Commission has focused exclusively on the size of the European company’s market share with the notorious many times-enforced rule of the 40 percent limit. When an EU firm exceeds a 40% European market share in a single product, it must stop its growth and divest what exceeds 40 percent.

This is also why there are no European firms among the largest in the world. The Commission has actually prevented growth in size by devising competition rules limited to the domestic theater only. This is what Draghi, with a certain understatement, meant when saying “we have only looked inward.”

Whenever businesses raised objections to this approach, saying that the arena of competition was worldwide and that was the market that the Commission should consider, a wall went up with the bureaucracy guardian applying the 40 percent rule without any ifs or buts.

Just as has been the case in so many other areas, where the conditions for competitiveness need to be rebuilt, the concern for consumer protection has ideologically taken precedence over business protection. But without businesses, as we have said so many times, there is no consumer.

Being able to change the perspective and take into account the real global target markets and not just the backyard would truly be a revolution.

In the coming weeks and months, we will see whether there will be awareness and an actual desire to change on these very relevant issues for the future of the Union and its ability to stand up to the challenge with the U.S., China, and prospectively, India.

The political campaign for the renewal of the European Parliament should focus primarily on this. The inattention at the international European level that has so far surrounded the work of Draghi and Letta does not bode well, but it is also up to us to work to ensure that this perception changes. It is in the interest of Italy and Italian businesses.

*Antonio Gozzi is advisor to the president of Confindustria on autonomy European strategy, the Mattei Plan and competitiveness.

This speech was originally published on Piazza Levante.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub

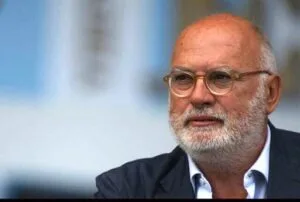

![[foto: imagoeconomica]](https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Imagoeconomica_1917240-scaled.jpg.webp)