Brussels – The risk of a collapse of the entire architecture of the Migration and Asylum Pact did not materialize in the end, with the vote of MEPs confirming all ten texts left on the table without too much of a fuss. The call for “political responsibility” on the eve of the vote by the eight chief negotiators worked and, despite several defections within the parliamentary majority, the Migration and Asylum Pact in its entirety (at least as far as the files that arrived at the negotiations with the EU Council) has passed the last potential major hurdle in the legislative process. Despite the radical change of all red lines of the initial position of the European Parliament, despite the imposition of the negotiating mandate of the 27 EU governments on almost the entire front, despite the splitting of two files and the post-agreement introduction of non-agreed amendments.

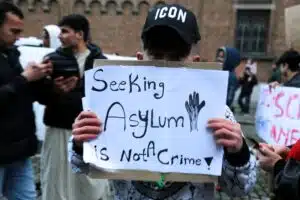

It is not an enthusiastic green light, apart from the Presidents of the Parliament and the Commission – Roberta Metsola and Ursula von der Leyen, respectively – who speak of a “historic day” for the migration and asylum system in the Union and a “huge achievement” after years of discussion, confrontation, and negotiations. They did not have the effect hoped for by civil society organizations – with dozens of protesters gathered outside the EU Parliament building and rioting from the stands shouting This Pact kills, vote no during the voting process – who were calling on MEPs to scupper the Migration and Asylum Pact. It was certainly not an easy vote, but there was never a moment of real crisis.

Just consider the final results: The Asylum Procedures Regulation (Fabienne Keller) passed with 301 in favor, 269 against, and 51 abstentions; the Crisis, Instrumentality, and Force Majeure Regulation (Juan Fernando López Aguilar) with 301 in favor, 272 against, and 46 abstentions; the Regulation for the Management of Asylum and Migration (Tomas Tobé) with 322 in favor, 266 against, and 31 abstentions; the Regulation Establishing a Border Return Procedure (Fabienne Keller) with 329 in favor, 253 against, and 40 abstentions; the Regulation on Screening (Birgit Sippel) with 366 in favor, 229 against, and 26 abstentions, the Regulation on the European Criminal Records Information System (Birgit Sippel) with 414 in favor, 182 against, and 29 abstentions, the Regulation on Eurodac (Jorge Buxadé Villalba) with 404 in favor, 202 against, and 16 abstentions, the Regulation on the New Resettlement Framework (Malin Björk) with 452 in favor, 154 against and 14 abstentions, the Regulation on Qualifications (Matjaž Nemec) with 340 in favor, 249 against and 34 abstentions, and the Directive on Reception Conditions for Applicants for International Protection (Sophie in ‘t Veld) with 398 in favor, 162 against and 60 abstentions.

If one looks at the voting decisions of Italian parties – in the complexity of the issue arising from ten files with specific aims and purposes – one can see, in general, a split between the forces of the governing majority, an alignment (not total) between the Democratic Party and Italia Viva, an opposition on almost the entire line by the 5 Star Movement. More specifically, the PD chose the line of opposition to the Migration and Asylum Pact, except the Regulation for the Management of Asylum and Migration (RAMM) – of which Pietro Bartolo was rapporteur-shadow for the S&D group – and the three ‘less securitarian’ dossiers (resettlement, qualifications, and reception). Iv’s head delegation, Nicola Danti, made the same choice but with the vote in favor also on crisis and repatriation. Fabio Massimo Castaldo, the only member of the other party of the now defunct ‘third pole’ (Azione), supported all files, just like Forza Italia MEPs. Speaking of the governing majority in Italy, FdI supported the Migration and Asylum Pact but not in its general approach according to RAMM (nor the three files that the PD supported) and abstained on the Regulation on Asylum Procedures, while the League chose the opposite line, voting against everything except for the ‘most securitarian’ files: repatriation, Regulation on the European Criminal Records Information System and Eurodac.

While waiting for the final go-ahead from the EU Council – expected on April 29 through a written procedure without a debate – it is worth remembering that the management of migration and asylum under the new Pact is overwhelmingly the result of agreements among the 27 EU governments. And the failure of the European Parliament on almost every line. In the Regulation for the Management of Asylum and Migration (RAMM) relocations of migrants between member states are no longer “primary measure of solidarity” as demanded by MEPs, but on par with financial contributions or support to third countries. In the Asylum Procedures Regulation (APR), national and EU lists of ‘safe third countries’ and the de facto detention for up to six months with no exemptions even for families with children under 12 were imposed by the Council. The so-called ‘pretense of non-entry’ has entered the Screening Regulation without exception, and the monitoring mechanism does not apply to border surveillance activities. The Eurodac Regulation is inconsistent with the standards applied to EU citizens according to the GDPR on biometric data collection and national authorities can indiscriminately collect photographic data of faces. Not to mention the Crisis and Force Majeure Regulation, which has seen enforced integration of instrumentalization regulation and no move to a mandatory relocation mechanism between member states in case of a crisis.

While waiting for the final go-ahead from the EU Council – expected on April 29 through a written procedure without a debate – it is worth remembering that the management of migration and asylum under the new Pact is overwhelmingly the result of agreements among the 27 EU governments. And the failure of the European Parliament on almost every line. In the Regulation for the Management of Asylum and Migration (RAMM) relocations of migrants between member states are no longer “primary measure of solidarity” as demanded by MEPs, but on par with financial contributions or support to third countries. In the Asylum Procedures Regulation (APR), national and EU lists of ‘safe third countries’ and the de facto detention for up to six months with no exemptions even for families with children under 12 were imposed by the Council. The so-called ‘pretense of non-entry’ has entered the Screening Regulation without exception, and the monitoring mechanism does not apply to border surveillance activities. The Eurodac Regulation is inconsistent with the standards applied to EU citizens according to the GDPR on biometric data collection and national authorities can indiscriminately collect photographic data of faces. Not to mention the Crisis and Force Majeure Regulation, which has seen enforced integration of instrumentalization regulation and no move to a mandatory relocation mechanism between member states in case of a crisis.

The basis of the Migration and Asylum Pact

The new Migration and Asylum Pact system is based on the relationship between solidarity and responsibility in the management of migrants among the Twenty-Seven. The former concept permeates the Regulation for the Management of Asylum and Migration (Ramm), which in no way overrides the cardinal principle of the 2013 Dublin Regulation, namely that the task of examining the asylum claim of a person who enters the EU territory irregularly lies with the first EU member state where they enters. Countries such as Italy, Greece, Malta, Cyprus, and Spain will be responsible for applications. Other member states that want to ‘Dublin’ (i.e., extradite) these migrants, including minors and those applying for reunification with siblings, will have to send a notification, no longer a reciprocal due process request with the agreement of the country of first arrival as is the case today. After the Regulation enters into force – 24 months after its publication in the EU Official Journal – the now famous mandatory solidarity mechanism for all Twenty-Seven (based on GDP and population) will be introduced, which equalizes three forms of solidarity: relocations of migrants, financial contributions or support to third countries. Contributions to member countries can be directed not only to reception systems but also to the funding of fixed and mobile border facilities through the Border and Visa Management Instrument (BMVI) and the Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund (AMIF). There is no mandatory relocation for migrants disembarked after search and rescue operations at sea, and for those under the RAMM procedure, there is no legal representation, only counseling.

The concept of accountability is related to the Asylum Procedures Regulation (APR ), which increases only those provided for countries of first entry. It will automatically apply if there is a risk for security threat issues – including unaccompanied minors – of “deception of authorities” or if the migrant person comes from a country with a recognition rate of less than 20 percent. Border procedures will provide de facto detention, with no exemptions even for families with children under 12, nor legal representation, nor a stay for appeals against most decisions (the exception is for inadmissibility of those based on the concept of “safe third country” and for unaccompanied minors). Crucial to this Regulation is precisely the “Safe Third Country” concept, for which both an EU list and national lists are provided to justify and expedite rapid returns out of the Union unless there are links of the individual person to the state in question that preclude their safety. New accountability obligations include completing the examination of an asylum application through the border procedure within six months(Apr), but also extending the period of responsibility for handling applications for 20 months and maintaining at 12 months that for search and rescue operations at sea (RAMM). The annual ceiling for border procedures, determined on the basis of a formula that takes into account the number of irregular border crossings and the number of expulsions in the previous three years, was set at 30,000 people.

What happens when migrant people arrive

Once migrants arrive at the Union’s borders, the Regulation on Screening of the Migration and Asylum Pact will provide a 7-day detention procedure for the division between regular (Ramm) or expedited (Apr) procedures for processing asylum claims. The so-called ‘fiction of non-entry’ has remained, meaning that anyone who screened in a special center will not be considered legally on the territory of the member state and, therefore, of the EU. Migrants will be detained as they will have to remain at the disposal of the authorities without the possibility of entering national soil. Some guarantees include the possibility for applicants to have access to a copy of the screening form and the preservation of the “relevant rules on detention” set out in the 2008 Return Directive (the revision contained in the Migration and Asylum Pact is the only dossier that is certain to fail). But the monitoring mechanism-which does not necessarily include NGOs but can do so at the discretion of states- does not apply to border surveillance activities(with normalization of racial profiling), and, if the state recognizes a security threat, it will be able to grant national authorities direct access to all data on the person in all databases.

(credits: Alessandro Serranò / Afp)

With regard to databases, according to the Eurodac Regulation, all migrants benefiting from temporary protection from the age of 6 will have to accept the collection of their biometric data, even though under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), processing is lawful only if the minor is at least 16 years old. Included in the expansion of data access for national authorities is the collection of photographic data of faces, effectively giving the green light to mass surveillance of people arriving on EU soil. Security alerts will be entered into the Eurodac database during the screening process, and border procedures will include a whole range of new categories-such as irregular border crossing-also through the revision of the Entry and Exit System Review Regulation.

What happens in a crisis

One of the most controversial items in the Migration and Asylum Pact is the Regulation for Crises, Instrumentality and Force Majeure, which deals with times when there is an exceptional or unexpected “mass arrival of people,” including following disembarkation after a search and rescue operation at sea. In fact, the Council negotiating position passed, which led to the inclusion of instrumentality (a Regulation that was initially a stand-alone and on which Parliament had not given the OK) for crises and force majeure in cases where “a hostile third country or non-state actor encourages or facilitates the movement of third-country nationals and stateless persons” towards the EU external borders “with the aim of destabilizing the Union or a Member State” by putting “the essential functions of a Member State at risk.” NGOs are excluded from this definition, but, in fact, only if they can demonstrate that their actions (at sea and otherwise) are not intended to destabilize, with clear risks of repercussions for the criminalization of solidarity.

Crisis situations also do not envisage compulsory relocations of migrants between member countrie but the same three modes of solidarity as in the RAMM Regulation (relocations, financial contributions, or support to third countries) will apply. Instead, derogations to the overall migration and asylum management system are triggered in this scenario: the recognition rate threshold for which people can be admitted to border procedures (under the APR Regulation at 20 percent) is raised to 50 percent in force majeure situations, 60/70 percent in crisis situations, and 100 percent in instrumentality situations. Again, families with children under the age of 12 are not excluded from the border procedures – the duration of which can be extended by an additional six weeks (compared to the 9 months in April).

English version by the Translation Service of Withub