Brussels – Serbia may be changing political course completely but the challenge to the European Union remains until the end of the government that President Aleksandar Vučić himself decided to end just over two months ago. On the eve of the vote for the renewal of Parliament scheduled for Sunday (Dec. 17)—after just a year and a half since the last election round—the first incumbent minister, Ana Brnabić, returning from Brussels after attending the EU-Western Balkans summit, made it clear in writing to the EU institutions that she does not recognize the legal value of the verbal commitments made in the context of the Pristina-Belgrade dialogue and that the de facto sovereignty of Kosovo will not be recognized either.

“The Agreement on the path to normalisation and the implementing annex is deemed acceptable only in a context that does not concern the de facto and de jure recognition of Kosovo,” reads the letter sent by the prime minister yesterday (Dec. 14) to the European External Action Service (EEAS). A position that is certainly not surprising, but for the first time put in black on white and addressed to the EU institutions. The opposition concerns, in particular, the “recognition of Kosovo’s membership in the United Nations, the UN system of organizations and agencies,” but also the “so-called territorial integrity” of the country that unilaterally declared independence from Belgrade in 2008: “The aforementioned document does not represent a legally binding treaty under international law,” reads the letter, which is in effect a slap in the face of the EU Commission President herself, Ursula von der Leyen, who in her trip to Belgrade on Oct. 31 had made it clear in front of President Vučić that the non-negotiable and extendable priority for Serbia is precisely the de facto recognition of Pristina as agreed in the EU-facilitated dialogue. “The alignment with this Declaration does not affect the fact that Kosovo remains an integral part of the territory of the Republic of Serbia,” the letter concludes.

Thirteen years of EU negotiations and diplomatic engagement to resolve one of the thorniest issues in Europe have gone up in smoke with a 12-line letter, signed by a premier who resigned at the behest of the president of the Republic (and former leader of her own party, the Serbian Progressive Party). It is hard, however, not to see this move not only as yet another provocation to Brussels, but more importantly as an internal propaganda message ahead of a vote that could for the first time put the ruling party in serious trouble. Particularly when one also considers Vučić’s words in a recent interview about the most sensitive issue for EU-Serbia relations, the alignment with EU foreign policy. The Serbian president ridiculed the other Balkan countries that have chosen this path and called the difficulties of the Ukrainian counteroffensive an opportunity for Belgrade to insert itself into a “more favorable” geopolitical environment after Western countries realized that “they cannot defeat Russia militarily.”

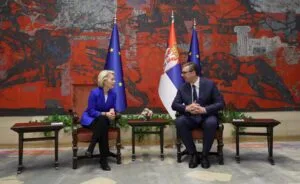

From left: European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Serbia’s President Aleksandar Vučić in Belgrade (October 31, 2023)

On Sunday, one of the most crucial election dates in recent history, particular attention will have to be paid to the performance of opposition forces that have remained fragmented to date. As analysts point out, the most concrete threat to Vučić’s power is represented by the Coalition “Serbia against Violence”, composed of 10 parties and civic movements ranging from the center to left-wing environmentalism and formed after the translation into (pro-European) political instances of the climate street protests that led to the shootings in May. The capital Belgrade is in particular the most contestable city, but also in the rest of the country protests have continued to fill the squares for months, and for the opposition to the ruling Sns party came today the most concrete opportunity to capitalize on a growing feeling of political dissatisfaction.

The complex 2023 between Serbia and Kosovo

The year 2023 had begun with Brussels leading a diplomatic offensive to reach a final understanding between the two sides that would also consequently resolve the continuing more or less violent incidents in northern Kosovo. It was on February 27 that the Brussels Agreement set out the specific commitments to be made by Serbia and Kosovo for the normalization of mutual relations: an 11-point proposal put forward by the EU and agreed upon by both leaders of the two Balkan countries at the endless meeting in the EU capital. Although the text was not signed, the agreement on the implementation annex (also unsigned, but with very heavy financial consequences if not complied with), reached after a 12-hour session of bilateral and joint meetings in Ohrid (North Macedonia) made it binding on Pristina and Belgrade.

Clashes between Kosovo Serb protesters and NATO Kfor mission soldiers in Zvečan, May 29, 2023 (credits: Stringer/Afp)

The still-unresolved tension between the two countries began on May 26, with the outbreak of extremely violent protests in northern Kosovo by the Serb minority over the taking office of the newly elected mayors of Zubin Potok, Zvečan, Leposavić, and Kosovska Mitrovica. Protests that turned on May 29 into guerrilla warfare that also involved soldiers from the international Kfor mission led by NATO (30 were injured, including 11 Italians). A situation triggered by the decision of Albin Kurti‘s government to force its hand and bring in special police forces to allow mayors elected on April 23 in a particularly contentious round to enter town halls: voter turnout tended to be derisory—around 3 percent—because of a boycott by Lista Srpska, the Serbian-Kosovar party close to Serbian President Vučić and also responsible for the filibuster to prevent ethnic Albanian mayors (apart from the Bosnian minority mayor of Mitrovica) from taking office. After the deployment in the Balkan country of 700 additional members of the Kfor reserve contingent and a week of apparent stalemate, new protests erupted in early June over the arrest of two protesters accused of being among those responsible for the violence in late May and for which Kosovar police are accused of mistreatment in custody.

Adding to an already tense situation was a further incident that inflamed the relations between Pristina and Belgrade: the arrest/kidnapping of three Kosovar policemen by Serbian security services last June 14. An event for which the two governments accused each other of trespassing by their respective police forces, in a border area between northern Kosovo and southern Serbia that is poorly controlled by Kosovar police and usually used by smugglers trying to avoid border controls. After weeks of continued calls for calm and de-escalation not being listened to by either Pristina or Belgrade, it became necessary for Brussels a new ‘buffer’ solution, namely convene an emergency meeting with PM Kurti and President Vučić to seek viable ways to back out of “crisis management mode” and get back on the path of normalization of relations undertaken between Brussels and Ohrid. Within days of the June 22 meeting in Brussels came Serbia’s release of the three Kosovar policemen, but for the time being nothing has been decided on new elections in northern Kosovo.

(credits: Armen Nimani / Afp)

Due to Pristina’s failure to take a “constructive attitude” toward de-escalation of tension, Brussels imposed “temporary and reversible” measures against Kosovo in late June, which also included suspending the work of the bodies of the Stabilization and Association Agreement. A roadmap with four stages was agreed on July 12 to remove these measures, but they are still in place (as criticized by the Kosovar president, Vjosa Osmani, at the last EU-Western Balkans summit). Within days of an unsuccessful high-level meeting in Brussels, however, the situation between Serbia and Kosovo escalated with the terrorist attack that began in the early hours of Sept. 24 near the Serbian Orthodox monastery in Banjska, when Kosovar police arrived to reports of an illegal checkpoint on the border with Serbia. The officers were attacked from several positions by a group of about 30 men armed with a heavy arsenal of firearms who, after killing one policeman and wounding two others, entered the monastic complex where pilgrims from the Serbian city of Novi Sad were staying. Clashes continued throughout the day during the “clearing operation”, in which three of the terrorists died.

Post-September 24 developments, however, have painted a much more serious picture than expected, with obvious ramifications in neighboring Serbia. As highlighted by a video filmed by a drone on the day of the attack, among the attackers outside the monastery was Radoičić, deputy head of Lista Srpska. While Kosovar police discovered a huge arsenal of weapons and equipment at the terrorists’ disposal, on Friday (Sept. 29) Radoičić himself confirmed that he had led the armed attack, putting the Serb leader in a difficult position. This confession has cast a long shadow not only over the participation of the Serb-Kosovar leadership in a strategy of destabilizing the country that has potentially been going on for years, but more importantly over Vučić’s ability to interfere in Pristina’s internal affairs in a more or less covert and violent manner. Adding to this are revelations about the presence also of Bojan Mijailović (one of the three killed bombers), a bodyguard of the head of the Serbian intelligence service, Aleksandar Vulin, and especially of Milorad Jevtić, a close associate of the Serbian president’s son, Danilo Vučić. According to the findings of an inquiry by Balkan Insight, the weapons used in the attack had been manufactured in Serbia in 2022 and some mortar shells and grenades had been repaired in Serbian state maintenance centers in 2018 and 2021.

From left: the prime minister of Hungary Viktor Orbán, and the president of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić, in Belgrade (July 8, 2021)

Finally worsening relations between Kosovo and Serbia was the U.S. warning of a Serbian “major military deployment” along the administrative border with “an unprecedented build-up of advanced artillery, tanks, and mechanized infantry units.” The threat did not materialize—according to PM Kurti, an annexation of northern Kosovo was planned with “a coordinated attack on 37 separate positions”—but the European Union has begun to reflect on the possibility of imposing the measures in force against Pristina against Belgrade as well. “We need to make sure that we make the best use of the tools the EU has to encourage both sides to contribute to a solution of the crisis,” EEAS spokesman Peter Stano had explained to Eunews. But the green light for the “temporary and reversible” measures against Serbia requires unanimity in the council and at the moment the only veto was placed by Vučić’s closest ally inside the Union: Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, who calls the scenario outlined by European officials and shared by the other 26 governments “absurd and ridiculous.”

English version by the Translation Service of Withub