Brussels – The Game. It looks inappropriate to define a “game” something that sounds like a Russian roulette played with human beings’ lives. All the 50,863 migrants who traveled along the Balkan route in 2020 (UNHCR data) know The Game. Especially the 22,550 people who – from May 2019 to date – have been victims of illegal pushbacks by an EU country in the context of border management operations that prevent a refugee from accessing the territory and the international protection (Danish Refugee Council data).

The Game starts in Bosnia and Herzegovina or Serbia – on the border with the ‘fortress-Europe’ – and the destination is Trieste railway station. You can “win”, if you manage to reach it avoiding the Croatian, Slovenian and Italian law enforcement authorities. On the contrary, if you are intercepted by the police, you are sent back from Italy to Slovenia, from Slovenia to Croatia, from Croatia to Bosnia or Serbia. The Croatian border policemen will use violence, in order to punish those who tried to “play” and to dissuade anyone else who is tempted to try The Game.

It is necessary to keep in mind the illegality of this practice, while we are looking for those responsible for the humanitarian crisis in Bosnia, following the fire at Lipa migrant camp on December 23. “The situation is unacceptable, the local authorities should behave like an aspiring EU Member State”, the High Representative of the European Union, Josep Borrell, repeated several times. The European commissioner for Crisis management, Janez Lenarčič, added that “humanitarian assistance would not be needed, if Bosnia implemented appropriate migration management”.

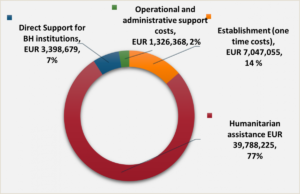

The government of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina certainly has its own responsibilities: it has been receiving 88 million euros since 2018 to address the immediate needs of refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants. At the same time, it seems that the EU Commission is playing the blame game. It is asking a divided and unstable country to solve a problem that the European Union does not want to tackle on the EU soil: namely, the management of migration flows along the Western Balkans route and the introduction of a coherent reception system for refugees and asylum seekers.

Not just a matter of money

In past few weeks, the EU Commission has been insisting on the fact that economic assistance to Sarajevo has been provided (88 million euros, plus additional 3.5 million). The International Organization for Migration (IOM) has received 76.85 million since June 2018. At the end of December 2020, 51.56 million euros were already spent on humanitarian assistance, support for Bosnian institutions and the setting up of seven reception centers. Almost two thirds of EU funds have already been spent in Bosnia.

The emergency tent camp in Lipa had a thousand places, but it was occupied by almost 1,500 migrants. Due to the unsuitable conditions for the winter, IOM announced that the camp would close on December 23, the same day when the fire broke out. In the Una Sana canton (North-West border with Croatia), there are four other temporary centers managed by IOM in the surroundings of Bihać. These include Sedra (430 places, occupied by 357 people in October 2020), Miral (700 places, all occupied), Borici (258 out of 580) and Bira, a center with 1,500 beds closed by the Bosnian authorities. The last two camps in the Sarajevo canton are overpopulated: Ušivak (860 people for 800 places) and Blažuj (2,874 out of 2,400).

To these centers, we have to add to the count two so-called “informal” camps spontaneously born on the Croatian border – Vučjak and Velika Kladuša – and the countless jungle camps in the woods and in abandoned industrial plants. Silvia Maraone, member of the Italian organization Ipsia Acli, testifies from Bosnia that “600 migrants who were in Lipa decided to go to the Sarajevo and Bihać temporary camps, while the other 900 are still in the burnt camp, where the local authorities set up temporary tents”. In Lipa “there is no running water and meals are distributed once per day by the Red Cross. We provide clothes and shoes, and we try to heat the tents”.

UNHCR estimates that migration flows along the Western Balkans route amount to 16,000 people in 2020 in Bosnia. “Since the spring of 2018, the Una Sana canton has become the bottleneck of the Balkan route“, Maraone explains. The country is “crushed between the incoming flows from Serbia and Montenegro and the flows of returnees from the Croatian border after the pushbacks”. The European Parliament has expressed significant concerns about the support offered to Bosnia by the EU institutions. “We gave Turkey 6 billion euros. Bosnia received only 88 million”, Maria Arena, chair of the subcommittee on Human rights, recalled during a conference organized last Friday (January 15) by her Italian colleague Pierfrancesco Majorino. “We cannot ask Bosnia to manage the migratory flows that we do not want to deal with on our soil”. Respect for human rights is the main concern: “It is not just a matter of money. In February 2020 a delegation of S&D MEPs went to Bosnia and asked for the end of pushbacks on the Croatian border”.

Skeleton in the closet of EU migration policy

Analyzing the humanitarian emergency along the Western Balkans route, the word ‘pushback’ echoes very often. It cannot be otherwise. As reported by the Italian network of associations “RiVolti ai Balcani”, two out of three migrants who were illegally rejected on the Croatian border have experienced violence and some kind of torture by the Croatian border police. On November 10, the European Ombudsman, Emily O’Reilly, opened an inquiry into a complaint from Amnesty International against the European Commission. The inquiry focuses on how the Commission ensures that the Croatian authorities respect fundamental rights in the context of border management operations.

The Italian journalist Nello Scavo reports that “the Croatian government, which is no longer able to deny the illegal pushbacks, claims that those responsible are not police officers, but rather armed civilians who patrol the border”. Just come back from the Bosnian-Croatian border, Scavo explains that “I did not find any armed civilian, but I was stopped, searched and sent back by Croatian police officers in riot gear on the Bosnian territory”. Moreover, non-EU nationals who try to enter the EU territory from Bosnia to Croatia have already entered previously, through Greece. The route to the heart of Europe forces them to go exit again and walk through North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Bosnia.

Those migrants who are able to evade Croatian police controls still have to face the Slovenian and the Italian borders, where they can be returned through informal readmissions, “agreements that date back to the war in the former Yugoslavia”, Scavo says. On July 24, the Italian Ministry of the Interior answered some urgent questions by MP Riccardo Magi, stating that there is no obligation to issue a written decision when a migrant is tracked down on the Slovenian border and readmitted to Slovenia, “even if they express the intention to seek international protection”. In the last seven months, Italy has readmitted 1,300 people to Slovenia and Slovenia has done the same to Croatia (10 thousand in total). “This is how the flow is blocked”, Gianfranco Schiavone, vice-president of the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI), explains. “This is the first time that the Italian government has admitted that they prevent asylum applications without issuing formal decisions”, Schiavone accuses. “This practice does not respect the rule of law”.

Those migrants who are able to evade Croatian police controls still have to face the Slovenian and the Italian borders, where they can be returned through informal readmissions, “agreements that date back to the war in the former Yugoslavia”, Scavo says. On July 24, the Italian Ministry of the Interior answered some urgent questions by MP Riccardo Magi, stating that there is no obligation to issue a written decision when a migrant is tracked down on the Slovenian border and readmitted to Slovenia, “even if they express the intention to seek international protection”. In the last seven months, Italy has readmitted 1,300 people to Slovenia and Slovenia has done the same to Croatia (10 thousand in total). “This is how the flow is blocked”, Gianfranco Schiavone, vice-president of the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI), explains. “This is the first time that the Italian government has admitted that they prevent asylum applications without issuing formal decisions”, Schiavone accuses. “This practice does not respect the rule of law”.

The aim of this whole strategy is to prevent thousands of people (with the right to ask for international protection) from accessing the EU territory and confine them to Bosnia. At the same time, other migrants are traveling north from Greece along the same route. “Bosnia has its responsibilities, but it is not clear why it should become the last impassable border with fortress-Europe“, Scavo urges. “The easier way to hide Europe’s problems is to reject these people and pay money to a non-EU country to keep them within their territory”. In this way, “the drama of a whole continent, once the cradle of human rights, that in Bosnia risks to become an intensive care for human rights”, is taking shape.

Critical voices in the European Parliament

The Italian MEP Pierfrancesco Majorino (S&D) is one of the most critical voices in Brussels against the EU migration policy. Interviewed by Eunews, he stated that “we must end the idea of Europe as a besieged fortress and stop the EU strategy to protect and externalize its borders to limit the alleged damage of immigration”. In Bosnia “we can see all the wrong choices taken at European level. The European Parliament can intervene to change the situation”. But how? “First of all, using the European Parliament as a sounding board: an MEP delegation who will travel to Bosnia very soon. At the same time, the Commission plan for migration should be rejected until it will be changed”.

Maria Arena, chair of the European Parliament’s subcommittee on Human rights, agrees: “Humanity, solidarity, human rights and protection are the European values we believe in. On the contrary, the watchwords for the EU Commission and the Council are internal security and border protection”. Arena denounces the New Pact on Migration and Asylum as “something we cannot accept the way it has been designed. There is no organized solidarity”. For this reason “the European Parliament has to fight and change the position of the European institutions. All progressive groups have to put an end to the European interests in unstable and fragile countries”.

It is not just a matter of money. It cannot be reduced to days of controversy, while thousands of migrants on the Croatian border are living in inhuman conditions, stuck in the snow and among frozen rivers. Accepting that The Game exists – on the skin of people who are looking for protection by the continent that once was the cradle of human rights – is already a defeat for the European Union.

Follow Federico Baccini’s newsletter, BarBalkans.