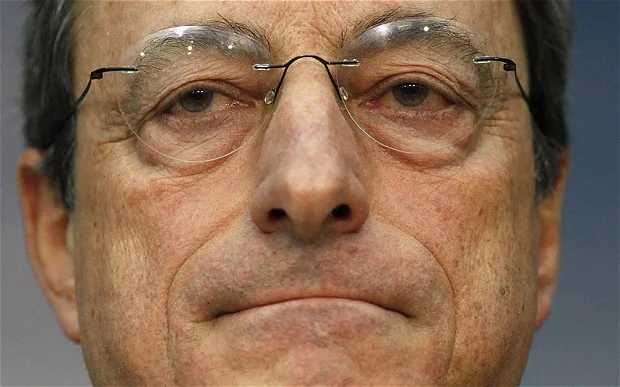

An open debate “about the benefits and the costs of living in a monetary union” is “actually welcome,” yet we cannot forget that “a good deal of this crisis is also due to the fact that we didn’t have enough integration.” Thus, the solution “rather than going back and re-nationalising our economies,” should be found in “moving forward towards greater integration.” This is the speech made by Mario Draghi in Brussels, at the end of the Governing Council meeting where, as expected, key ECB interest rate unchanged at 0.25 percent, as everyone expected – given that in June the ECB is releasing a series of macroeconomic indicators on the Eurozone, and that will be the time for deciding whether it will be necessary to act, even with “unconventional instruments,” Draghi underlined, to cope effectively with risks of a too prolonged period of low inflation.

According to the ECB President “in the last 20, 25 years we have achieved much through our integration,” but “we can’t really rest on the memory of past achievements,” we need to move forward. Moreover, we need to understand that integration was very good “for efficiency” but “the equity dimension” of the process was somehow left aside. Now Europe needs to show, if it really wants to win over euroscepticism, that it is able to “create growth and jobs together with stability.”

We do not need to leave the path of reforms in the process, even in those countries, such as Italy, where the benefits from reforms are not visible yet. “if you look at many countries, take Spain, for example. Or take even Greece. Take Portugal. Take Ireland. They have done many important structural reforms. They are continuing this effort. And you see in all four countries clear signs of recovery,” said Draghi, “Those reforms are, indeed not easy, difficult and painful. But there seems to be, as the examples have shown, very little alternative.”

The commitments under the Stability Growth Pact are not easy to be achieved too, in countries like Italy and France for instance, which are asking postpone the structural balance (3 percent debt-to-GDP ratio). “I don’t know whether it is possible or not,” said Draghi, “what is clear is that we had rules originally, and in the early 2000s these rules were broken by countries like France, Germany and Italy,” and this event brought other countries to fell free of “piling up stocks of debt that were shown to be unsustainable by the crisis,” as well as “some levels of deficits were unsustainable.”

So, in Draghi’s view there is an easy conclusion: “Undermining the credibility of existing rules is never a good policy.”